31. Ptosis (Blepharoptosis)

- Definition: Ptosis is diagnosed when the upper eyelid hangs more than one or two millimeters below the upper limbus of the cornea when the patient is awake and in the forward gaze.

Though the left eye is seen to be ptotic, the story of this patient needs some elaboration. This was a case of Bilateral ptosis of advancing years which was operated on both sides by suspending the eyelid (the tarsal plate), (see para 2 fig. 1) to the frontalis muscle by an unabsorbable suture. So far it has worked on the right side but has failed on the left. The picture is reproduced to stress that surgery for ptosis is a matter of training and familiarity and should not be undertaken by ‘occasional surgeons’ ! This procedure was wrong.

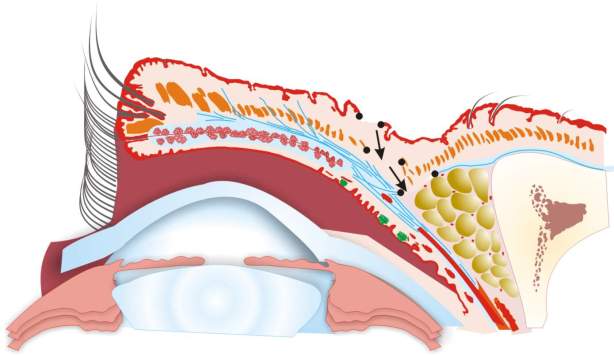

- Essential anatomy:

- The eyelid contains a structure called the tarsal plate which constitutes its skeleton and is made up of dense fibrous tissue. Anterior to the tarsal plate is the orbicularis oculi muscle which circles both the eyelids and is attached to the orbital bones mostly in the orbit’s medial half. This muscle is subcutaneous. At about the level of the upper edge of the tarsal plate there is a fold in the skin of the eyelid which appears like a crease when the eye is open so that when the eye is closed there is no shortage of skin.

- In the upper eyelid two muscles are attached to the upper edge of the tarsal plate, the levator palpabrae superioris and the Muller’s muscle. Of these the levator is longer, arises from deep inside the orbit, is in the shape of a broad ribbon, though it starts as a tendon. In the distal one third it becomes aponeurotic and it is this aponeurosis which is attached to the tarsal plate. The Muller’s muscle is much smaller and lies posterior to the aponeurosis of the levator. The levator is the main elevator of the eyelid while the Muller’s muscle is much weaker yet exerts some action and therefore can raise the eyelid by one to two millimeters (Fig. 4). The action of the levator can lift the eyelid up to 15 mm (Fig. 3).

- To the upper edge of the tarsal plate is also attached a fascia called the orbital septum. Its other attachment is to the frontal bone and behind it lies a pad of fat called the supra-orbital pad of fat (Fig. 4). This pad of fat together with orbital septum and the levator aponeurosis sometimes tends to prolapse in the elderly (the baggy eyelids of the later years).

- Nerve supply: The orbicularis oculi is supplied by the facial nerve which when paralysed does not allow the eye to be closed because normally the orbicularis oculi squeeze the eyelids to close the orbital fissure. This inability can lead to exposure keratitis. The levator palpabrae superioris is supplied by the oculo motor nerve which also supplies all the external muscles of the eyeball except the lateral rectus which is supplied by the abducent nerve and the superior oblique supplied by the trochlear nerve. The paralysis of the ocular motor nerve in any part from its nucleus to its intra-orbital course leads to a condition called ophthalmoplegia and also produces ptosis. The Muller’s muscle is supplied through the autonomic nervous system, its sympathetic supply coming from a plexus of nerves around the carotid artery. A paralysis of this supply will lead to a very mild ptosis with constriction of the pupil which will not dilate even in the dark (Horner’s syndrome, please see note at the end of the chapter). The normal orbital fissure is maintained by the tone of the orbicularis oculi on the one hand and the levator palpabrae superioris on the other. During sleep the levators’ tone is reduced considerably leading to the eyelid covering the whole eyeball.

- Types of Ptosis: Disruption of the function of the oculomotor nerve leading to ptosis has already been mentioned. If this disruption is reversible, ptosis will automatically correct itself. If the oculomotor nerve function does not recover even though retinal function is normal, and the patient is leading a normal life, treatment of ptosis must be undertaken guardedly because the upward protective rotation of the eyeball, which is a normal reflex to protect the cornea when the eyelid is opened forcibly is absent (Bell’s phenomena). It is advised that under these circumstances if surgery is undertaken some form of protection of the eye with glasses is required. Ptosis can also occur from local causes in the eyelid itself for e.g. due to the weight of a tumour including neurofibromatosis or lymphangiactesis or other vascular anomalies. Scarring in the eye by whatever causes can also restrict the excursion of the levator and cause ptosis. In Graves’ disease (exomphthalmos) or in proptosis when the eyeballs are not symmetrically affected the eyelid on the less affected side might appear ptotic but is in fact not. This usually goes by the name of pseudoptosis.

- Primary ptosis or ptosis per se: Cause for the primary ptosis by and large lies in the musculo-aponeurotic structure of the levator (see note on Horner’s Syndrome at the end). A dysplastic or poorly developed muscle belly causes congenital ptosis which may be recognized at birth or in early infancy or in later childhood. A degenerated and therefore lengthened or a fragmented aponeurosis of the levator causes ptosis in later years though a lax aponeurosis is not entirely uncommon in older children through adulthood. Occasionally fragmentation of the levator aponeurosis can lead to a near avulsion of the aponeurosis from the tarsal plate. A post traumatic affection of the levator complex is strictly speaking a secondary occurrence but is included here because the approach and treatment for the condition is similar to as in the two causes mentioned earlier.

- Physical examination: The excursion of the levator in the fixed forward gaze position is measured by blocking the action of the frontalis muscle by placing one hand over the supra-orbital ridge to prevent any false movement and then asking the patient to open his or her eyes or eye. If one eye is involved, a comparison is readily available. Measurement is done in millimeters by a foot rule or a caliper. In another test when a light is directed towards the eye it shines as a dot in the centre of the eye (in the pupil). When the distance between this dot and the lower edge margin of the upper eyelid is less than 3 mm ptosis is said to be present.

- Classification and clinical basis of surgical treatment: It is customary to divide the movement of the eyelid into three groups: 1) 0-5 mm; 2) 5-10 mm; 3) 10 mm and above upto 15 mm. A measurement of upto 5 mm only, or usually one or two millimeters or sometimes absence of any movement at all is almost always caused by a dysplastic or a poorly developed levator. A ready reckoner (after Berke) is given below indicating the type of operation most likely to succeed

| Group 1 | 1-5 mm | Suspension of the lid from the frontalis muscle by fascia or an alloplastic material |

| Group 2 | 5-10 mm | Resection of muscle and/or shortening of the aponeurosis |

| Group 3 | 10-15 mm | Repair of the levator aponeurosis |

In group 1 (with less than 5 mm movement) an operation that will suspend the eyelid one or two mm below the superior limbus in a static manner will need to be performed because no amount of shortening of the levator will endow it with any additional dynamic movement. The agent used for the suspension is attached to the frontalis at the upper end and the tarsal plate at its lower end and the patient is trained to consciously contract the frontalis by way of training whenever possible. In the event the mechanics of this operation are both static and dynamic. In very small children this is difficult. In group 2 movement between 5-10 mm particularly in children, a decision to shorten the muscle can be taken on the table after the muscle is exposed and if the aponeurosis is found to be normal. The muscle here is somewhat active and shortening may help. In most cases group 2 and 3, particularly in the elderly where movement between 5 mm to 15 mm is present the aponeurosis is the reason for the ptosis and it is shortened, reefed or reattached to the tarsus if it is avulsed as the case demands. In infants when ptosis is severe whether unilateral or bilateral when the eyelid or eyelids cover most of the cornea disuse retinal atrophy (amblyopia) is a distinct possibility and an operation for suspension of the eyelid and some form of protection (glasses) needs to be employed.

Basic diagrams of the surgery for ptosis with the sagittal section of the eyelid with the patient lying supine.

The skin is entered at just above the tarsal plate.

The orbicularis is visualized and is separated along its transverse fibers.

The tarsal plate is visualized and the orbital septum is opened.

Plane of dissection is now anterior then superior and later backwards in relation to the levator apparatus.

If the procedure involves only the aponeurosis, deeper resection is not needed.

If muscle resection or reefing is planned, dissection proceeds backwards.

The diagram below shows the plan for a static (part dynamic) suspension of the tarsal plate to the frontalis muscle. In this operation small incisions are taken above the eyebrow to access the frontalis muscle and a tunnel is made through the eyelid below the orbicularis through which either fascia or an alloplastic material is threaded up to the tarsal plate which is exposed with small incisions. The fascia is sutured to the tarsal plate and then by judging the tension sutured to the frontalis muscle.

- Figure 10: The last arrow head shows the site of anchoring of the fascia to the tarsal plate.

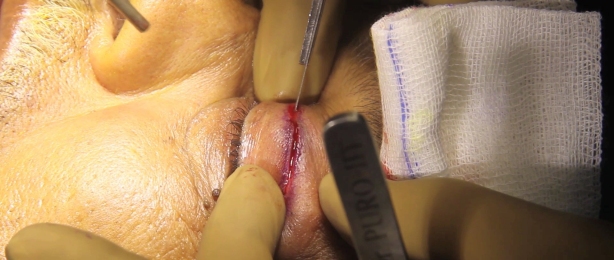

The surgical steps in a representative case (already shown in para 1 under ‘definition’) was operated under local anaesthesia. This allows the surgeon to judge the results of his procedure because the patient is conscious.

The incision is marked 8-10 mm above the lid margin possibly at the site of the future fold that the eyelid will form.

Local anaesthetic required is very small in quantity and therefore does not distort the landmarks. Usually includes appropriate doses of adrenaline and is given several minutes before the surgery is begun in order that the patients cooperation is fully available and the effect of vasoconstriction is complete.

The skin is incised. Haemostasis is achieved if required. At this stage the transversely disposed fibres of the orbicularis oculi muscle (supra-tarsal portion) are visualized and are separated along their fibres if necessary with a sharp incision and then are retracted.

Upon retracting the orbicularis muscle, the orbital septum arising from the tarsal plate and going superiorly to attach to the frontal bone is visualized. It is seen here as a tissue whiter than the surrounding retracted orbicularis muscle.

The orbital septum here is exposed and appears yellowish white because of the fat in the supraorbital fossa which is shining through it.

The orbital septum has now been incised. Please note the two incised leaves of the orbicularis oculi muscle on either side and the whiter tarsal plate extending from the lid margin.

Below this layer of fat the crucial step of identifying the levator palpaebrae superioris (LPS) is now being taken. A gentle tug on this structure will result in movement of the eyelid upwards.

Depending upon the procedure that is to be performed. The LPS is now to be anchored to the tarsal plate. The photograph shows a needle going through the tarsus about 2 mm below its superior edge which will then be sutured to the shortened levator aponeurosis. This is usually called a trial stitch.

The patient is then made to sit up after the trial stitch has been proved to be adequate and the rest of the LPS has been anchored to the tarsus so that the effect of gravity on the lid can be gauged and the real success of the procedure can be ascertained. As can be seen here, the lid is just above or touching the upper limbus of the cornea.

It is essential that there is no over correction and the lid can close completely both actively as well as passively (as in sleep) without any tension because of the repair.

Shrirang Purohit from Mumbai, who has provided all the clinical photographs reproduced so far makes a point that in cases where suspension of the tarsal plate needs to be either done by an autologous tissue or a biological substitute, a plastic surgeon is more likely to use fascia because of his familiarity with this harvest for other plastic surgical procedures. In the past the fascia used to be harvested from the thigh by way of a fasciotome but now some surgeons have started opting for temporal fascia, an adequate length of which is usually available. The advantage of using temporal fascia lies in it being in an adjacent area. A series of photographs contributed by Nitin Mokal of Mumbai are reproduced below.

A case of congenital ptosis with total absence of movement of the eyelid due to a dysplastic or an undeveloped LPS. This is ideally suited for a frontalis → facial sling anchored to the tarsus. The child is old enough to be trained to convert his frontalis action for opening the eyelids. Please see table for choice of operation in an earlier part of this chapter (after Berke). See figure 9.

Incisions are made just above the eyebrows to expose the attachment as well as the flat muscle belly of the frontalis muscle.

The temporal fascia is being harvested. Adequate breadth and length of this tissue will allow its use for both sides.

The fascia is threaded by creating a blind tunnel under the skin and the orbicularis oculi and has appeared in an incision in the eyelid just above the tarsal plate.

Note: Nitin Mokal is using a single flat piece of fascia unlike conventional photographs shown in books where a criss-cross pattern of facial slings are normally used. He first anchors the fascia to the tarsus, lets it hang from the other incisions by way of applying mosquito forceps so that his hands are free to suture it to the frontalis muscle at a correct level.

A late post-operative result with ptosis corrected, the eyelids hovering just around the upper limbus of the cornea and a full closure at will.

Horner’s Syndrome (also less frequently called as Claude-Bernard Syndrome) results from disruption of the sympathetic nerve supply of the Muller’s muscle. The disruption can be 1) central (hypothalamospinal tract) 2) by way of pre-ganglionic pressure, as from a tumour of the apical lobe of the lung (Pancoast tumour) or 3) because of post-ganglionic affections around the carotid artery, as in a dissecting aneurysm of that vessel causing pressure. Once these or similar causes are ruled out, the ptosis in Horner’s syndrome which is very mild and is diagnosed by the presence of a constricted pupil, which does not dilate even in the dark, is treated with resection of the Muller’s muscle which is ideally approached, through the conjunctiva because it lies posterior to the levator aponeurosis and is the first structure to be encountered when the sub-conjunctival space is entered.

Acknowledgment: The diagram of the sagittal section of the eyelid is universally common in almost all books dealing with this subject and is therefore can be called to be in the public domain for many years. The figure used here is from a latest ‘anniversary edition’ of Grays’ Anatomy (Churchill, Livingstone) but it is adapted here with some changes in the colour scheme to suit the purpose of this chapter.

Plastic Surgery as a speciality has not only produced many a stalwarts who went on to excel in various sub-specialities but it also welcomed many a specialists from other fields who became standard bearers of plastic surgeons in various sub-specialities. John Mustardé was an ophthalmic surgeon (like Woolfe who taught plastic surgeons the technique of full thickness skin grafts) whose work on the surgery of eyelids has remained a standard text for more than a generation of plastic surgeons. Here is a short biographics sketch.

John Clark Mustardé 1916 – 2010

Jack Mustardé, as he was always known, was a Scottish plastic surgeon. Born and educated in Glasgow where he qualified in medicine, his early training was in ophthalmlogy He joined the Army in 1940 and was sent to Egypt as an eye surgeon. He was taken prisoner by the Germans but repatriated because of ill health in 1943. He then trained under Sir Harold Gillies as a plastic surgeon and, after the war, obtained consultant posts, first in Nottingham, later at Canniesburn Hospital in Glasgow. He wrote extensively on ophthalmic plastic surgery, including the textbook “Repair and Reconstruction in the Orbital Region” and also “Plastic Surgery in Infancy and Childhood”, in which he described a new technique for correcting prominent ears.

After a distinguished career, Mustardé retired in 1991, but subsequently set up the International Reconstructive Plastic Surgery Ghana Project in Accra, where he spent alternate months for many years. It is now a flourishing teaching unit and serves the whole country, a fitting memorial to a great surgeon and charismatic character.